The great Albanian leader George Castriota Scanderbeg, who led a successful defense of his country for twenty-five years against the Ottoman onslaught in the mid-fifteenth century, died on January 17, 1468. His remarkable feat defended Western Civilization at a time when the Turks threatened to extend Islamic rule across Europe. Today marks the 555th anniversary of his death. Scanderbeg's military prowess was celebrated during the centuries that followed. Among those who immortalized him was the famous American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.

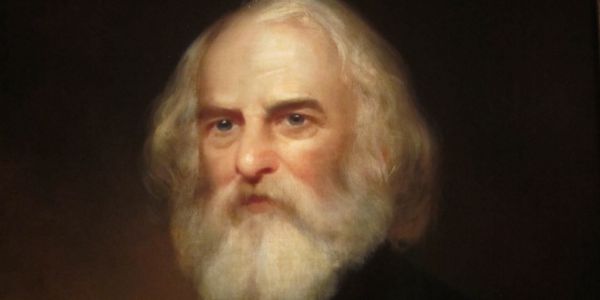

American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807-1882) authored many of the most popular poems in nineteenth-century American literature. Descendant of an old New England family, Longfellow traveled extensively throughout Europe before he became professor of modern languages at Bowdoin College from 1829 to 1835. After the death of his first wife in 1835, Longfellow returned to Europe, where he met Frances Appleton, who became his second wife and served as the model for the heroine of his prose romance Hyperion published in 1839. From 1836 to 1854, Longfellow served as professor of modern languages at Harvard. He achieved great fame, especially for his long narrative poems including Evangeline (1847), The Song of Hiawatha (1855), The Courtship of Miles Standish (1858), and Tales of a Wayside Inn (1863). The latter volume included one of his best-known poems “Paul Revere’s Ride” featuring some of the most famous verses in nineteenth century American literature:

Listen my children and you shall hear

Of the midnight ride of Paul Revere.

Another of Longfellow’s masterpieces was his poetic translation of Dante’s Divine Comedy published in 1867. After his death, he was honored as the first American writer whose bust was placed in the Poet’s Corner in Westminster Abbey in London.

His poem “Scanderbeg,” commemorating the great Albanian national hero George Castriota Scanderbeg who fought to defend Christendom from the onslaught of the Ottoman Turks in the fifteenth century, is contained in part 3 of Longfellow’s Tales of a Wayside Inn, as the Spanish Jews Second Tale.

Longfellow undertook this large-scale literary project in part as a way to deal with the grief over the loss of his second wife who died in 1861. Longfellow originally intended to call the collection The Sudbury Tales, but he worried it sounded too similar to Geoffrey Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales. At the suggestion of his friend, Massachusetts senator Charles Sumner, he changed the title of the book to Tales of a Wayside Inn.

In the manner of Geoffrey Chaucer’ Canterbury Tales and Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decameron, the poems included in the collection are told by a group of people set in the tavern of the Wayside Inn in Sudbury, Massachusetts, located only twenty miles from the poet’s home in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The inn had been a favorite location for revelers from Harvard College, where Longfellow had taught, before it closed when its owner, Lyman Howe, died in 1861. To research the setting for his book of poems, Longfellow visited the Wayside Inn in 1862, together with his friend and publisher James Thomas Fields. The poet referred to it as “a rambling, tumble-down building.” Longfellow saw it as the perfect setting for his collection of epic poems. The Wayside Inn did not reopen for business in 1897. The American industrialist Henry Ford then purchased the inn in 1923, restored it, and donated it to a charitable foundation. It still operates as an inn and a historic site today: www.waysideinn.org

Most of the stories were derived by Longfellow from his wide reading and extensive travels — many of them have their origins in legends from continental Europe, and others from American sources. Among these was the legend of the great Albanian national hero George Castriota Scanderbeg who successfully defended his country against invasion by the Ottoman Turks for a quarter of a century from 1443 to 1468. Longfellow’s poem recounts the great deeds of the Albanian leader who staved off the Islamic assault.

Tales of a Wayside Inn was first published on November 23, 1863, with an initial print run of 15,000 copies. Longfellow’s poem “Scanderbeg” would become the most famous literary account of the deeds of the great Albanian hero in English literature. His poem was first translated into Albanian by the great Albanian-American scholar Bishop Fan Noli in 1916.

THE BATTLE is fought and won

By King Ladislaus the Hun,

In fire of hell and death’s frost,

On the day of Pentecost.

And in rout before his path

From the field of battle red

Flee all that are not dead

Of the army of Amurath.

In the darkness of the night

Iskander, the pride and boast

Of that mighty Othman host,

With his routed Turks, takes flight

From the battle fought and lost

On the day of Pentecost;

Leaving behind him dead

The army of Amurath,

The vanguard as it led,

The rearguard as it fled,

Mown down in the bloody swath

Of the battle’s aftermath.

But he cared not for Hospodars,

Nor for Baron or Voivode,

As on through the night he rode

And gazed at the fateful stars,

That were shining overhead;

But smote his steed with his staff,

And smiled to himself, and said:

“This is the time to laugh.”

In the middle of the night,

In a halt of the hurrying flight,

There came a Scribe of the King

Wearing his signet-ring,

And said in a voice severe:

“This is the first dark blot

On thy name, George Castriot!

Alas! why art thou here,

And the army of Amurath slain,

And left on the battle-plain?”

And Iskander answered and said:

“They lie on the bloody sod

By the hoofs of horses trod;

But this was the decree

Of the watchers overhead;

For the war belongeth to God,

And in battle who are we,

Who are we, that shall withstand

The wind of his lifted hand?”

Then he bade them bind with chains

This man of books and brains;

And the Scribe said: “What misdeed

Have I done, that, without need,

Thou doest to me this thing?”

And Iskander answering

Said unto him: “Not one

Misdeed to me hast thou done;

But for fear that thou shouldst run

And hide thyself from me,

Have I done this unto thee.

“Now write me a writing, O Scribe,

And a blessing be on thy tribe!

A writing sealed with thy ring,

To King Amurath’s Pasha

In the city of Croia,

The city moated and walled,

That he surrender the same

In the name of my master, the King;

For what is writ in his name

Can never be recalled.”

And the Scribe bowed low in dread,

And unto Iskander said:

“Allah is great and just,

But we are as ashes and dust;

How shall I do this thing,

When I know that my guilty head

Will be forfeit to the King?”

Then swift as a shooting star

The curved and shining blade

Of Iskander’s scimitar

From its sheath, with jewels bright,

Shot, as he thundered: “Write!”

And the trembling Scribe obeyed,

And wrote in the fitful glare

Of the bivouac fire apart,

With the chill of the midnight air

On his forehead, white and bare,

And the chill of death in his heart.

Then again Iskander cried:

“Now follow whither I ride,

For here thou must not stay.

Thou shalt be as my dearest friend,

And honors without end

Shall surround thee on every side,

And attend thee night and day.”

But the sullen Scribe replied:

“Our pathways here divide;

Mine leadeth not thy way.”

And even as he spoke

Fell a sudden scimitar-stroke,

When no one else was near;

And the Scribe sank to the ground,

As a stone, pushed from the brink

Of a black pool, might sink

With a sob and disappear;

And no one saw the deed;

And in the stillness around

No sound was heard but the sound

Of the hoofs of Iskander’s steed,

As forward he sprang with a bound.

Then onward he rode and afar,

With scarce three hundred men,

Through river and forest and fen,

O’er the mountains of Argentar;

And his heart was merry within,

When he crossed the river Drin,

And saw in the gleam of the morn

The White Castle Ak-Hissar,

The city Croia called,

The city moated and walled,

The city where he was born,—

And above it the morning star.

Then his trumpeters in the van

On their silver bugles blew,

And in crowds about him ran

Albanian and Turkoman,

That the sound together drew.

And he feasted with his friends,

And when they were warm with wine,

He said: “O friends of mine,

Behold what fortune sends,

And what the Fates design!

King Amurath commands

That my father’s wide domain,

This city and all its lands,

Shall be given to me again.”

Then to the Castle White

He rode in regal state,

And entered in at the gate

In all his arms bedight,

And gave to the Pasha

Who ruled in Croia

The writing of the King,

Sealed with his signet-ring.

And the Pasha bowed his head,

And after a silence said:

“Allah is just and great!

I yield to the will divine,

The city and lands are thine;

Who shall contend with Fate?”

Anon from the castle walls

The crescent banner falls,

And the crowd beholds instead,

Like a portent in the sky,

Iskander’s banner fly,

The Black Eagle with double head;

And a shout ascends on high,

For men’s souls are tired of the Turks,

And their wicked ways and works,

That have made of Ak-Hissar

A city of the plague;

And the loud, exultant cry

That echoes wide and far

Is: “Long live Scanderbeg!”

It was thus Iskander came

Once more unto his own;

And the tidings, like the flame

Of a conflagration blown

By the winds of summer, ran,

Till the land was in a blaze,

And the cities far and near,

Sayeth Ben Joshua Ben Meir,

In his Book of the Words of the Days,

“Were taken as a man

Would take the tip of his ear.”

For more on the life of Scanderbeg, we recommend Scanderbeg: A History of George Castriota and the Albanian Resistance to Islamic Expansion in Fifteenth Century Europe by A.K. Brackob.