As the multi-national Ottoman Empire began to fall apart in the aftermath of the Russo-Turkish war of 1878, the Albanian people faced the peril of being absorbed into the surrounding newly formed nation-states of Southeastern Europe. Albanian leaders met at Prizren in 1878 to devise a strategy to defend their national rights. The Formation of the Albanian National Consciousness a new book by acclaimed historian A.K. Brackob explores the origins of this movement that ultimately led to the creation of the modern-day Albanian nation-state.

Had a national consciousness failed to develop prior to the crisis of 1878, the creation of the national movement that not only sought to protect Albanian lands against foreign annexation but also strove to unite the four Albanian vilayets (Ottoman Administrative Districts) into a single autonomous administrative unit would not have been possible. The development of a national consciousness during the decades preceding 1878 built the foundation for the national movement that culminated in the creation of the League of Prizren and ultimately led to the formation of the modern independent Albanian nation-state in 1912.

The Albanian national consciousness did not suddenly develop in response to the crisis of 1878. The Albanians are the descendants of the ancient Illyrians who inhabited the Balkan peninsula since pre-Homeric times. The antiquity of the people in their homeland is an important element in the Albanian ethnic identity as they are distinguished by being the oldest inhabitants of the peninsula and because they speak a language derived from ancient Illyrian, distinct from that of their Slavic and Greek neighbors. Only in the fifteenth century, however, did a sense of ethnic identity develop among the Albanians during their resistance to the Ottoman invasions. This resistance, led by George Castriota Scanderbeg, brought Albanians of various regions, speaking different dialects, together in a common struggle against foreign aggression. This struggle helped define the ethnic identity of the Albanians. In book VI of his Commentaries, Pope Pius II cites a letter ostensibly written by Scanderbeg and sent to the Prince of Taranto that helps to illustrate this sense of ethnic awareness:

Our ancestors were Epirotes, of whom came that Pyrrhus whose attack the Romans could hardly resist, who took by force of arms Tarentum and many other Italian towns. You cannot set against the valiant Epirotes, the Tarentines, a sodden race born to catch fish. If you say that Albania is part of Macedonia, you concede us far nobler ancestors, who penetrated with Alexander into India, laying low with incredible success all the nations who opposed them.

Whether or not the letter itself is authentic, the sentiment it expressed certainly is. Albanians recognized that they were a distinct group of people with a unique heritage.

During the early part of the nineteenth century, several Albanian intellectual leaders played a critical role in creating a national movement to prevent the partitioning of Albanian lands among the neighboring Balkan states.

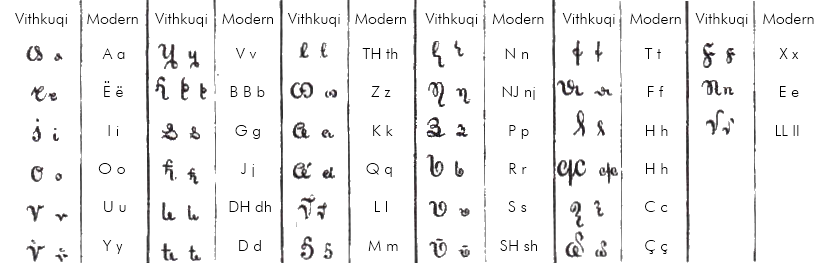

The most important leader of the Albanian national movement in the early part of the nineteenth century was Naum Veqilharxhi (1797-1854). Veqilharxhi joined the Greek revolutionary organization, Filiki Hetaria, and participated, along with many of his countrymen, in the rebellion of 1821 in the Romanian principalities. Western ideas of nationalism had a strong impact on Veqilharxhi. He expressed these clearly when he wrote, “The time has come to rouse ourselves and to reconsider our way of life, to change our course more radically and follow the example of the advanced nations throughout the world.” To do this, Veqilharxhi realized that the development of the written language was essential. He developed an original Albanian alphabet and published the first Albanian primer, Evetor, in Romania in 1844. He was martyred in 1854, poisoned by agents of the Patriarch.

Konstandin Kristoforidhi (1827-1895), another key figure in the formation of the Albanian national consciousness, played a particularly important role in the development of a written language. Born in Elbassan, in central Albania, in 1827, Kristoforidhi paid particular attention to the study of language. “If the Albanian language is not written,” he argued, “in a short time there will be no Albania on the face of the earth, nor will the name Albania appear on the map of the world.” His life’s work was the compilation of an Albanian dictionary

Another important figure whose work is discussed in The Formation of the Albanian National Consciousness is Pashko Vasa (1825-1892). His book, Études sur l’Albanie et les Albanais, is the most important historical work of the Albanian national renaissance. Published in French and German in 1878, it asserted the national rights of the Albanians and the goals of the League of Prizren to a European audience. One of Vasa’s principal concerns was to refute Greek claims to the territory of southern Albania, and “to prove the antiquity of the Albanian people and their own existence outside of the Hellenic family.”

Another chapter in the book deals with the efforts of Albanian intellectuals to overcome the religious divisions in the country. The principal way they did this was to stress Albanian culture and offer patriotism as a substitute for religious belief. Pashko Vasa’s poem, Mori Shqypni a mjera Shqypni [O Albania, poor Albania], is one example of this:

Awake, Albanians, from age-long slumber

On church and mosque rely no longer,

You owe no duty to priest and pope,

To love your country is your only hope.

His proclamation that “The religion of the Albanians is Albanianism” became the motto of the League of Prizren. Other attempts to stifle the effects of religious division included Sami Frashëri’s call for the establishment of an Albanian Orthodox Church to free it from Greek and Slavic domination, and Naim Frashëri’s support for the Bektashi, a pantheistic Moslem sect which incorporated many elements of Christianity, as a means of achieving a religious unification.

The efforts of all of these Albanian leaders and many more that led to the development of the Albanian national consciousness are explored in The Formation of the Albanian National Consciousness. Despite the repression of the League of Prizren by Ottoman forces in the spring of 1881, the national struggle of the Albanian people to preserve their territory and culture enhanced their sense of national consciousness. The temporary reestablishment of Ottoman political control could not blunt this achievement. Thus, the formation of the Albanian national consciousness in the period preceding the crisis of 1878 was of vital importance for the future of the people by creating the basis for the foundation of the Albanian nation-state in 1912.

The book is essential reading for anyone wishing to understand Albanian history. A.K. Brackob is a noted specialist in East European history. His other books include Scanderbeg: George Castriota and the Albanian Resistance to Islamic Expansion in Southeastern Europe in the Fifteenth Century, Mircea the Old: Father of Wallachia, Grandfather of Dracula, and Dracul – Of the Father: The Untold Story of Vlad Dracul. The Formation of the Albanian National Consciousness is available at histriabooks.com and from all major book retailers.